Rex V. Brown: A Life

Rex Brown was a devoted family man, a pioneer in the field of decision theory, a warm and brilliant wit, an infuriating contrarian, an irrepressibly generous friend and father, an ever-trying (in both senses) husband, and – if his gracious handling of several terminal diagnoses is any indication — the very definition of a trooper. He died on July 25, 2017 at the age of 83.

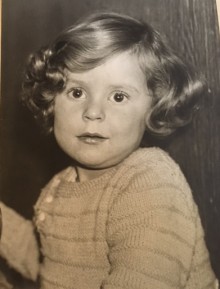

He was born on September 25, 1933 in London to Diane Vandesteene Brown, a Belgian immigrant to England. He was raised by Diane and her husband Leon Brown, who Rex learned years later was not his biological father. While his relationship with Leon was marked by tension and mistreatment, he was utterly devoted to his mother and they had a warm, loving relationship. He was also close to his sister Ines.

He grew up during World War II, and almost didn’t survive the blitz; he was recovering from tuberculosis in a London hospital when it was bombed, but managed to crawl out of the building holding his toothbrush. Years later, as an adult, he worried about not having enough to eat and always ordered more at restaurants than anyone could consume.

He was born into Roman Catholicism, but during the war a Jehovah’s Witness came to his mother’s door and converted Diane and her two children. After adolescence, Rex left the religion and became a disciple of atheism, then agnosticism.

He was smart, curious and mischievous from a young age, and won a scholarship to attend Minchendon Grammar School. He excelled, though he always felt he was falling short, something he attributed to his father’s emotionally abusive behavior. He nevertheless earned a place at Queens College at Cambridge University, where he experienced some of his most fulfilling years. (This was after a two-year stint in the British Navy, for which he had volunteered, he said, to “toughen” himself up.)

At Cambridge University, he was active in theater and briefly considered pursuing acting as a career. In 1956, he organized one of the first student trips from England to the University of Moscow (Russian, which he learned in the Navy, was among his several languages). He reported being approached for espionage by both the West and the East, but – in deference to his academic interests – declined all offers.

He later got a doctorate at Harvard Business School, where he met a number of like-minded colleagues in the fledgling field of decision analysis. Several of his publications, including an early textbook, are considered classics in the field. He ended up leaving academia in the 1970s to become a professional decision analyst for several consulting firms, starting in Michigan and then the D.C. area. He co-founded the company Decision Science Consortium in Reston, VA.

[To read Rex’s professional obituary, by Jon Baron, click here (and scroll down.)]

On the personal front, he enjoyed a number of girlfriends throughout his twenties and early 30s –and remained close friends with several of them for the rest of his life. But his goal was always to become a father, so he set about finding a wife. In 1965, his Harvard roommate introduced him to Dalia Levy, an Israeli interior designer, and within three weeks they were engaged. (Family lore has it that visa issues sped up the process.) They married three months later, and remained married for the rest of his life. He converted to Judaism so they could raise their children Jewish.

His first daughter, Michele, was born in 1962 from an earlier relationship with Gay Moran, who raised Michele in England.

His next three daughters, with his wife Dalia, were born in 1966 (Karen) and 1969 (twins Tamara and Leora.)

As much as he enjoyed and found satisfaction in his profession, nothing came close to the joy, commitment, and love he felt for his children, and later, his grandchildren. He had long wanted to raise children with an affection that would represent the opposite of how his father had raised him, and he succeeded. He could never understand why anyone would not want children, and as many as possible.

He doted on his seven grandchildren – Keenie and Shane (from Michele), Sam and Lucy (from Karen), Kobe (from Tamara), and Hazel and Jackson (from Leora.) He often said he felt incredibly lucky with his sons-in-law, including Karen’s husband Sean, Leora’s husband John, Michele’s husband Eamon, and Tamara’s partner Anthony.

He was often the center of family gatherings, singing Tom Lehrer tunes, cracking inappropriate, politically-incorrect jokes, and managing to bring his wit and generosity into every conversation. Most people adored him. He loved to challenge established opinions, to make people see the uncomfortable side of any issue (which could drive his family mad). He also liked to defend Quixotic endeavors – and remained convinced that feature-length “hologram movies” were an untapped goldmine.

He was dedicated to supporting other people’s ambitions and dreams, often using his own money, connections, or creativity to help them, and this included people he didn’t know that well. He once brought a little girl home with him from the bus stop to play with his children because she looked like she was lonely. (He also made a habit of donating to public broadcasting several times a year, because he never remembered his previous donation.)

His absentmindedness was infamous; he may be the only person who left the gas nozzle in his car as he drove away from the station…twice. He often left the house in his slippers, and once checked into a conference hotel … in the wrong city (he forgot he had a connecting flight).

His lack of self-consciousness, combined with a deep desire to learn new things, led him to a number of unconventional pursuits: he’d go to drum circles in Takoma Park and dancing at a lesbian bar in Northampton, he took guitar lessons alongside his daughters, and he could always be found dancing with his hands making odd-looking circles at any party gathering.

Although he “semi-retired” in the 1990s, he remained committed to the science of decision-making, and spent his last decades writing papers and books about how the layperson can make better decisions. When he wasn’t with his children or grandchildren, he was at his computer, writing his professional tomes. This was a common source of frustration for his wife Dalia, but she knew it was also what fed his vitality.

In 2011, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer – after he used his decision analysis know-how to convince his doctor to test him. He had surgery to remove the tumor, and – in a feat that amazed most doctors – went into remission. Over the next few years, he had a number of additional health issues, including several orthopedic surgeries and diabetes, but he was always able to bounce back and continue with professional work, trips with family, and many probing conversations with friends and progeny.

In late 2015, his kidneys started to fail, and after traveling to Florida to attend his daughter Leora’s wedding, he began dialysis. In early 2017, he was diagnosed with a recurrence of pancreatic cancer, and chose not to treat it. He entered hospice care at home.

Throughout this medical turmoil, he kept up regular visits to the swimming pool and weight machines, took trips out on his backyard boat, and remained fully engaged in family life. He also expressed great relief at having finally come out from under the poor self-esteem his father had instilled, and declared that he believed he was actually a pretty impressive guy.

Up until the final month of his life, he was putting the finishing touches on his last book, “The Art and Science of Making Up Your Mind: Decision Theory for the Everyman.” He learned a week before his death that it would be going into production.

.

After he wrung every last drop out of his physical being (he lost about 75 pounds in 4 years), his irrepressible spirit left his body. He was surrounded by his family when he took his last breath.

.

As he often said in his final days, “I am not too bothered about shuffling off this mortal coil. I feel quite complete. I am just sorry that, if I’m not mistaken, a number of people will miss me.”

He got that right.